Unravelling the intriguing risk of finished tasks

From all clear to almost too near

By Maximilian Peukert, Aviation Psychologist and Human Factors Specialist, and Eivind Martinsen, ATCO and Group Manager, Air Navigation Services of Sweden (LFV).

It is a normal day at work. The Air Traffic Controller (ATCO) has been 40 minutes in position, being responsible for a sector handling arrival traffic to a major airport, along with other traffic such as overflights.

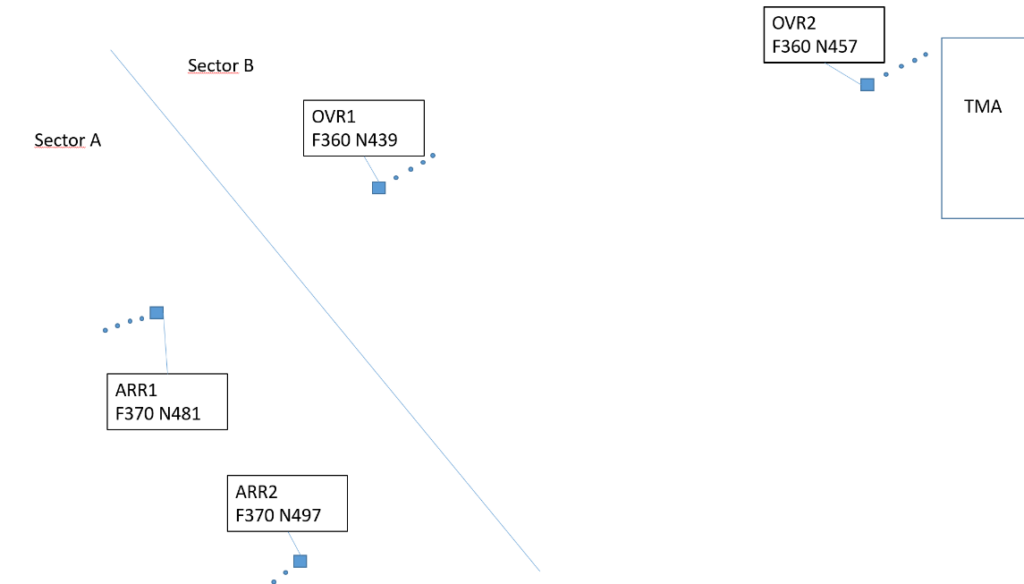

The relevant traffic situation involved four aircraft: two arrivals (ARR1 and ARR2) and two overflights (OVR1 and OVR2) as illustrated in Figure 1 below. Unexpectedly, and to the surprise of the ATCO, a separation loss occurred between ARR1 and OVR1. The chain of events leading to this incident is described in the following passages.

Figure 1 – Traffic Picture during the chain of events

ARR1 and ARR2 were flying eastbound from sector A to sector B for landing within the TMA. OVR1 and OVR2 were flying westbound at FL360. The ATCO in sector A assessed that sector B would need to take action regarding the sequencing of ARR1 and ARR2, and handed the two aircraft over to sector B. ARR1 with a turn release “T”, ARR2 with a full release “F”, to allow sector B to take action within sector A’s airspace. Simultaneously, sector B assessed that OVR1 would meet ARR1 within sector A, and thus changed OVR 1 to sector A’s frequency. ARR1 and OVR1 were now on frequencies not corresponding to the sector they were physically in, and on different frequencies.

The ATCO in sector B identified a need for sequencing ARR1 and ARR2, and to descend both these aircraft below OVR2 to have the freedom to do so. OVR1 was just transferred to sector A. The label for ARR1 obscured both the label for the now redundant (sector state “redundant”, meaning a less visible colour) OVR1, and the potential conflict between these flights presented on ARR1’s flight leg.

Initially, E3 misinterpreted “T” as “F” and descended ARR1 to FL350 to facilitate later sequencing by getting below the OVR2 at FL360. The conflict between ARR1 and OVR1 was presented in CARD (Conflict and Risk Display), which E3 did not notice as the focus was on the radar screen. Thirty seconds after the descent clearance was given, ARR1 left FL370, triggering an STCA alert. E3 performed recovery by reascending ARR1 to FL370. The action came too late to maintain separation.

ARR1 and OVR1 passed each other with around 3 NM distance.

Good intentions come with risks

So, what happened? Somehow the ATCO lost track of the situation. Even after receiving high amount of training, ATCOs are still human beings, and performance might be limited by very basic brain processes that can lead to cognitive traps. From a psychological perspective, a few explanations for the near miss are possible. Common cognitive traps are referred to as biases and heuristics. Heuristics are mental shortcuts or rules of thumb, which aim to simplify decision-making and problem-solving activities. Our brain is efficiency-oriented, it seeks to spend less mental effort. Quicker judgements and decisions are aimed for. And this efficiency-orientation is usually rewarded as it mostly leads to a good outcome. But only mostly, not always. Rapid solutions to complex problems can lead to biases and errors due to their reliance on simplifications and generalizations. Few common heuristics are:

- Availability Heuristic: Tendency to rely on readily available information to make judgments about the likelihood or frequency of events.

- Anchoring and Adjustment Heuristic: Tendency to rely heavily on the first piece of information encountered when making decisions and then adjust from that initial anchor.

- Confirmation Bias: Tendency to search for, interpret, and remember information in a way that reinforces preexisting beliefs and reject information that contradict.

- Hindsight Bias: Tendency to see events as having been predictable after they have already occurred.

But there are even more efficiency-oriented cognitive processes. Have you ever encountered the tendency to remember things better when tasks are not yet completed? Or, in other words, that unfinished tasks tend to stick in your memory? This phenomenon is known as the ‘Zeigarnik effect’, named after Bluma Zeigarnik, firstly describing it almost a century ago. Conversely, completed tasks are more likely to fade from consciousness. In the near miss case, ARR1 had been cleared to descend below a third aircraft. The ATCO might have had the impression that the original conflict of the earlier flight had been resolved, and attention shifted to other tasks. The ARR1-related task felt completed. Thus, OVR1 was unintentionally neglected.

Cognitive turbulences can occur at any time

Heuristics, Biases, and the Zeigarnik Effect are undoubtedly products that aim to enhance higher brain efficiency. This is not inherently bad. These phenomena are helpful in many situations, allowing us to make quick decisions or freeing up mental resources for new tasks. However, when applied inappropriately or in situations requiring careful analysis, they can lead to negative outcomes, earning them the label of cognitive traps. Operators should be aware that heuristics, biases, and the Zeigarnik effect impact us in all aspects of life. Our brains tend to efficiency, leading to favour impressions that support our perception and to clear completed tasks to make room for new ones.

The human brain is a marvellously complex organ that offers a multitude of possibilities that cannot simply be replaced by computer technology. However, the brain is an enigma that still leaves many questions unanswered. But one thing is certain: it sometimes presents us with challenges. How can ATCOs protect themselves from these completely evolutionary disadvantages? Certainly, system support, training, and awareness are key aspects, but ultimately, we are only as good as our brains can be.

For more information or training and discussion opportunities, please contact the Human Performance Management Work Group via Safety@CANSO.org.