Fatigue and fatigue risk management in ATM – Wake up and spot the difference!

By Lea-Sophie Vink, Head of Human Performance and Human Factors, Austro Control, and Maximilian Peukert, Human Factors Specialist, LFV Sweden.

In July 2017, Air Canada flight 759 to San Francisco came within 100 meters of landing on a taxiway where aircraft were awaiting take off. This could have been one of the most catastrophic accidents of all time. One of the key contributing elements cited in the Aircraft Incident Report was fatigue. Prior to the pandemic, attention was already turning to addressing the safety risks inherent with ATCO fatigue. Through the pandemic different types of threats emerged such as ‘underloading’ due to boredom and monotony of having no air traffic. These issues were also linked to the formation of fatigue. In Europe, EASA awarded a multi-year research tender to several institutions to undertake a widescale academic study. New Eurocontrol guidelines have been issued to ANSPs and one of the most frequent questions we receive to our workgroup is about how organisations can tackle or implement Fatigue Risk Management (FRM) policies and solutions.

But what exactly are the issues?

Fatigue has become a prominent subject, evident through the increasing number of scientific papers and regulations addressing this topic. However, fatigue is often regarded as problem and result at the same time, whereas it should be viewed as an umbrella term encompassing different phenomenon. Terms such as ‘sleepiness’ and ‘vigilance’ are all somehow related to fatigue, but not entirely. Mental fatigue can be examined from a temporal perspective, distinguishing between acute and chronic fatigue.

Chronic fatigue pertains to a persistent and prolonged state of weariness that extends beyond the usual recovery period. It presents normally as longer term physical and mental health issues and sometimes as burnout. It is often protected by occupational health and safety and working time rules.

Acute fatigue refers to a temporary state of reduced vigilance and attention resulting from prolonged wakefulness or extended mental exertion. Acute fatigue is a true safety risk for ANSPs because it usually presents as reduced reaction time, cognitive impairment, and sometimes behavioural issues. These can lead directly to impaired performance at the workstation. Once individuals are already suffering from chronic fatigue, this can further exacerbate acute fatigue.

The distinctions between the two are of significant relevance as the approaches and countermeasures to address acute and chronic fatigue may differ. Organisations should consider these differences. By acknowledging the nuanced nature of fatigue and its manifestations, organisations can develop fatigue management practices that address concerns related to acute fatigue and chronic fatigue.

One of the primary methods of managing fatigue is to used rostering. However, rostering mainly refers to the operational process of ensuring sufficient staff members are available to fulfil tasks within regulatory requirements. Rostering is often referred to as the prescriptive approach since companies adhere to predefined rules set by regulators. The issue with this approach is that these rules may not fully consider actual fatigue levels and fatigue variations, and fatigue-related hazards are typically identified only after an incident occurs. There is a common misconception that rostering is equivalent to a Fatigue Risk Management System (FRMS). Rostering is one part of a FRMS, it can be thought of as one element of a set of mitigation practices designed to reduce the risk of fatigue in the Ops room or towers, but it is by no means the only mitigation available.

In contrast, an FRMS is a specialised process designed to proactively manage fatigue hazards, like a safety management system (SMS). The purpose of an FRMS is to identify and assess potential risks associated with fatigue before and during operational activities. Unlike rostering, which focuses on staffing requirements, an FRMS considers factors contributing to fatigue and actively mitigates those risks. Other mitigations can include: training, team resource management, occupational health and safety policies, active monitoring of how fatigued people are and regular feedback and improvement initiatives.

By implementing an FRMS, an organisation can proactively identify and assess potential fatigue-related risks, ensuring that appropriate measures are in place to prevent incidents. This approach emphasises the importance of managing fatigue hazards throughout the entire operational process rather than reacting to them after an occurrence. With an FRMS in place, organisations can go beyond existing worktime regulations. With the flexibility to stretch work times gained comes the responsibility that the organisation has to prove safety to the regulator from a fatigue standpoint.

FRMS is a data-driven process. This implies that it is based on actual fatigue data collected regularly through research studies, interviews, or the collection of fatigue reports. Usually there is no single way, but a data collection method must be chosen based on the requirements and purpose of the FRMS. Overall, the FRMS may include several activities, such as

- Fatigue risk assessments: Organisations conduct fatigue risk assessments to identify potential risks associated with fatigue. This involves evaluating the workload, work schedule, and other factors that can impact fatigue levels.

- Work schedule management: Organisations manage work schedules to ensure that operators have sufficient rest periods between shifts. This may include implementing shift rotations, providing adequate breaks during shifts, and limiting the number of consecutive working days.

- Education and training: Organisations provide education and training to front-line operators on the risks associated with fatigue and strategies for managing fatigue. This may include providing information on sleep hygiene, nutrition, and exercise.

- Communication and support: Organisations foster a culture of open communication and support to encourage operators to report any concerns related to fatigue.

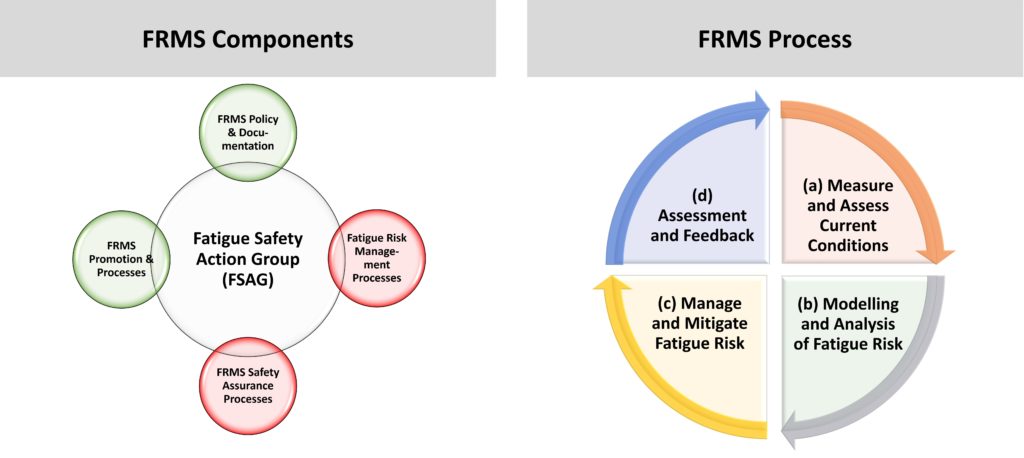

Figure 1 – Components and Process adapted from FAA AC120-103A: Fatigue Risk Management Systems for Aviation Safety (AC 120-103A – Fatigue Risk Management Systems for Aviation Safety (faa.gov))

Adoption of a FRMS is highly recommended by ICAO and CANSO for all ANSPs. Increasingly data-driven solutions are becoming available and several large-scale fatigue research projects are underway around the world. If you would like assistance understanding how to implement, or design, an FRMS, or a presentation of what is going on in the world of FRMS, please contact the Human Performance Management workgroup and we would be happy to support.